How Minimalism Became Luxury: The Real Meaning Behind “Owning Less”

✨Key Points

Minimalism began as rebellion — art stripped of ego, not a lifestyle for elites.

Over time, it was rebranded as a luxury identity, fueled by marketing and class disparity.

Real minimalism — like wabi-sabi — values imperfection, humility, and presence.

The problem isn’t owning things. It’s performing emptiness to prove worth.

Coming Back to Seattle — and Seeing “Less” Everywhere

I just got back to Seattle after a month and a half in Europe — six countries, countless planes, buses, and trains.

Perfect public transportation, cheap coffee and warm pastries, cafés that feel like quiet galleries, apartments styled like beige palettes, and effortlessly chic people who somehow know exactly how to mix vintage with modern trends.

Everywhere I went, I kept seeing the same thing — modern minimalism everywhere.

Not the kind you feel in your bones when life gets simple, but the kind you curate, price, and post.

And now, back in Seattle, I’ve started to notice it slowly appearing here too — in shop windows, cafés, even the way people dress.

It made me wonder about the real minimalism meaning — when did simplicity turn into a symbol of status?

Or is it actually a reflection of people trying to spend less and live within their means?

Traveling through Europe, it became clear how minimalism became luxury — a reflection of taste shaped as much by economics as by aesthetics.

Think about the royal influence in places like Spain, Austria, and France. People there have inherited a deep understanding of style — generations raised among art, architecture, and quiet refinement.

And then there’s the old-money influence; imagine inheriting an apartment in the heart of Vienna or Madrid, filled with vintage furniture and family heirlooms that never go out of fashion.

Yet somehow, they still choose less — clean lines, muted tones, intentional spaces. It’s the same mindset that’s now shaping global trends like No Buy 2025, where people are consciously stepping back from overconsumption in search of balance.

Somewhere between the busy cafés and the quiet galleries, I couldn’t help but see minimalism and capitalism intertwined — a philosophy once rooted in restraint, now sold back to us as a lifestyle aspiration.

Rich People Cosplaying Poverty

Minimalism is just rich people cosplaying poverty. If you have money, this is minimalism. If you’re poor, this is just failure.

That sounds harsh, but it’s true. Minimalism itself isn’t the problem — the problem is how it’s been repackaged as a luxury identity. It’s no longer about simplicity; it’s about signaling taste.

Writer and critic Kyle Chayka, in his book The Longing for Less, says, “Minimalism today is more about the illusion of control than the freedom from it.”

“Less is more”: Everywhere we hear the mantra. Marie Kondo and other decluttering gurus promise that shedding our stuff will solve our problems.

People are no longer escaping consumerism — they’re just upgrading to a calmer, more expensive version of it.

The “less” we celebrate online isn’t always liberation.

Sometimes, modern minimalism is just rebranded privilege — living with less because you can, not because you have to.

The Radical Origins: Minimalism as Rebellion

Let’s rewind.

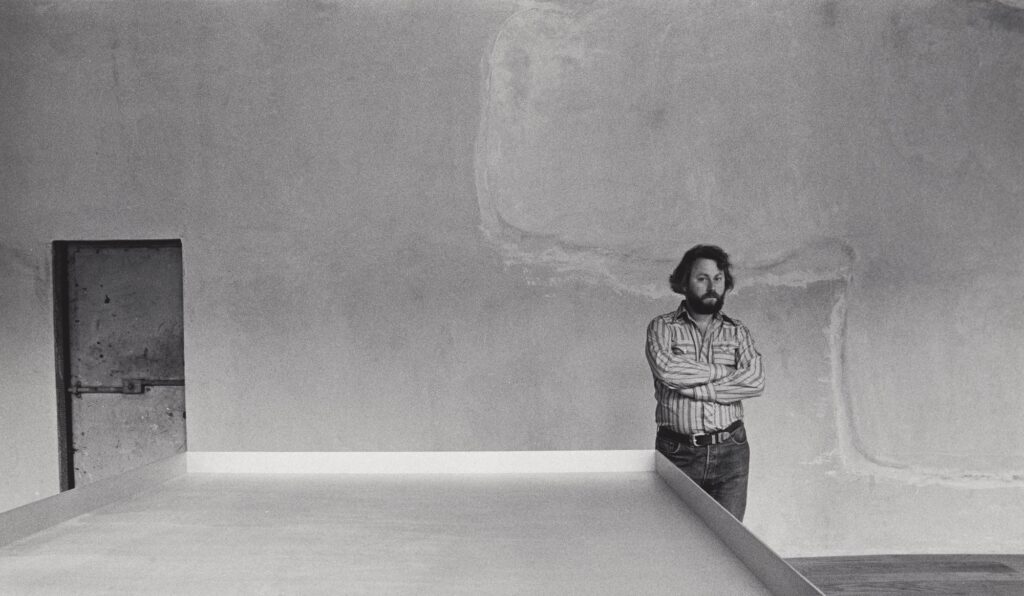

Minimalism in the West began in the 1960s as a radical artistic code.

Think Donald Judd, Dan Flavin — artists who worked with raw materials, industrial steel, neon lights, and no hidden meaning.

It was an in-your-face rejection of expressionism and symbolism, the dominant postwar art movements that glorified emotion and chaos.

Minimalism then was loud, political, and deliberately stripped of sentiment. It wasn’t cozy.

It wasn’t about “decluttering your life.”

It was about tearing down everything unnecessary — the noise, the ego, the excess.

Donald Judd once wrote:

“A shape, a volume, a color, a surface is something itself. It shouldn’t be concealed as part of a picture.”

To him, honesty of form was the point. A work didn’t have to tell a story — it just had to exist.

Artists like Agnes Martin painted grids that were almost meditative, forcing you to see calmness as resistance.

Modern minimalism was once rebellion — not a lifestyle choice, not a Pinterest mood board.

Brutalism: Doing More With Less, and Doing It for Everyone

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, post-war Europe was experimenting with a different kind of “less.”

Brutalism — a movement in architecture defined by exposed concrete, communal housing, and a clear social purpose.

It didn’t pretend to be neutral. It shouted politics. It built homes for everyone, showing structure instead of hiding it.

In London’s Covent Garden, locals fought back against demolition plans that would have erased their public housing in favor of modernist redevelopment.

Those fights were not about design — they were about survival, belonging, and community.

Brutalism was never meant to be beautiful. It was meant to be honest. As architect Alison Smithson once said:

“Brutalism tries to face up to a mass production society and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work.”

That’s miles away from the modern minimalism we see on Instagram today — perfectly curated, softly lit, and far removed from the raw rebellion it once was.

From Protest to Product

Over time, this powerful minimalist aesthetic was rebranded.

Clean lines and empty spaces became the luxury canvas for influencers, brands, and showrooms.

What was once an avant-garde protest became a quiet status symbol.

By the 1990s, design magazines and Scandinavian furniture brands — from Muji to IKEA’s more curated lines — began turning “simplicity” into a product.

By the 2010s, social media finished the job: minimalist interiors became a currency of taste.

As critic Bell Hooks once noted, “When we aestheticize simplicity without ethics, we turn humility into a commodity.”

Modern minimalism doesn’t reject consumerism — it depends on it. It’s not about doing more with less; it’s about buying less, but better. And “better,” of course, usually means expensive.

Freedom or Privilege? The Double Standard of ‘Less’

When influencers show off capsule wardrobes or minimalist luxury furniture, it’s framed as freedom.

But when someone has almost nothing because they’re broke, no one calls that minimalism.

Now, the meaning is completely different because one is a choice and the other isn’t.

Minimalism tells you to own less to feel free. But if you already live with less because you can’t afford anything else, it doesn’t feel like freedom at all.

As writer Caitlin Dewey once put it, “Minimalism is what happens when rich people get tired of having stuff.”

Even the idea of buy fewer, buy better quietly assumes that you can afford to replace your cheap clothes with €100 linen shorts or oak furniture. The narrative of liberation hides behind price tags.

Tiny Homes, Big Business

Take tiny homes. In theory, they’re a smart, sustainable response to the housing crisis.

In reality, developers market them as luxury lifestyle choices.

In France and the Netherlands, people now pay more than €80,000 for one of these “minimal living pods.”

What started as a movement for affordable, eco-friendly living is now a playground for architects selling curated scarcity.

They’re no longer solving housing problems — they’re rebranding them.

A 250-square-foot house can now come with heated floors, smart lighting, and marble countertops.

It’s still small — just not simple anymore.

As one architect joked in an interview with Dezeen, “Minimalism has become maximalism for people who hate clutter.”

And that line captures modern minimalism perfectly — it’s still consumption, only quieter.

The Green Illusion: Consuming Mindfully While Consuming More

Then there’s all the green, mindful consumption — bamboo forks, thin wooden chairs, reusable water bottles.

But people are still buying. They’re just buying aesthetics.

The eco-friendly market exploded in the past decade, worth over $300 billion globally.

“Mindful shopping” is the new indulgence.

Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman once said, “We shop for meaning the way we once prayed for it.”

That’s exactly what’s happening. Sustainable minimalism sells us peace — not through stillness, but through another transaction.

You’re not less consumerist; you’re just a consumer with taste.

Wabi-Sabi: A Minimalism That Doesn’t Need an Audience

Now, here’s where I want to pause and highlight that not all minimalism is the same.

In Japan, minimalism is tied to wabi-sabi, an ancient philosophy about impermanence, humility, and the beauty of what’s unfinished or imperfect.

And it’s not about showing off how little you own while following a trend — the true spirit of the owning less movement is about living intentionally, not performing simplicity for others.

It’s about how much you can live without performing it.

Wabi-sabi teaches that cracks, wear, and imperfection are what make things beautiful. The idea isn’t to curate absence — it’s to honor impermanence.

Japanese architect Tadao Ando once said: “I create emptiness for people to fill with their own thoughts.”

That’s the kind of minimalism that doesn’t care for likes.

It doesn’t need marble tables or muted wardrobes. It’s lived, not staged.

Maybe that’s what the West has missed — the humility of simplicity without spectacle.

Minimalism, Capitalism, and Mental Space

It’s easy to understand why people crave minimalism. Life feels cluttered — mentally and physically.

Digital overload, constant updates, endless comparison. “Decluttering” promises a sense of control.

But capitalism, as always, finds a way to monetize the cure.

The self-help industry sells us “calm,” productivity apps market “focus,” and home brands market “clarity.”

As essayist Jenny Odell wrote in How to Do Nothing,

“We long to be free from the attention economy, but we try to buy our way out of it.”

That’s the paradox — you can’t purchase peace. And yet, that’s what minimalist marketing asks us to believe.

So If You Can Afford That €30K Coffee Table…

Please, think twice and wonder why you’re buying it.

If the answer is “because it feels right,” maybe that’s fine. But if the answer is “because it fits my aesthetic,” maybe pause.

Minimalism was never meant to be about erasure or perfection. It was meant to question — to reveal what really matters when you strip everything away.

Owning less isn’t automatically profound. But owning with intention — that still is.

Final Reflection: What Minimalism Could Still Be

Maybe minimalism isn’t dead — maybe it’s just buried under too much branding.

Maybe it still lives quietly in people who mend what they have, who share space, who appreciate what’s already here.

In that sense, minimalism isn’t an aesthetic — it’s a practice. A quiet reminder that our worth doesn’t live in what we own, even if the world keeps trying to sell it back to us.